It all started in the summer of 2023, when author and infectious-disease physician Dr. Chris van Tulleken was promoting his book, Ultra-Processed People. While writing it, van Tulleken spent a month eating mostly foods like chips, soda, bagged bread, frozen food, and cereal. “What happened to me is exactly what the research says would happen to everyone,” van Tulleken says: he felt worse, he gained weight, his hormone levels went crazy, and before-and-after MRI scans showed signs of changes in his brain. As van Tulleken saw it, the experiment highlighted the “terrible emergency” of society’s love affair with ultra-processed foods.

Wilson, who specializes in working with clients from marginalized groups, was irked. She felt that van Tulleken’s experiment was over-sensationalized and that the news coverage of it shamed people who regularly eat processed foods—in other words, the vast majority of Americans, particularly the millions who are food insecure or have limited access to fresh food; they also tend to be lower income and people of color. Wilson felt the buzz ignored this “food apartheid,” as well as the massive diversity of foods that can be considered ultra-processed: a category that includes everything from vegan meat replacements and nondairy milks to potato chips and candy. “How can this entire category of foods be something we’re supposed to avoid?” Wilson wondered.

So she did her own experiment. Like van Tulleken, Wilson for a month got 80% of her daily calories from highly processed foods, not much more than the average American. She swapped her morning eggs for soy chorizo and replaced her thrown-together lunches—sometimes as simple as beans with avocado and hot sauce—with Trader Joe’s ready-to-eat tamales. She snacked on cashew-milk yogurt with jam. For dinner she’d have one of her beloved Costco pupusas, or maybe chicken sausage with veggies and Tater-Tots. She wasn’t subsisting on Fritos, but these were also decidedly not whole foods.

A weird thing happened. Wilson found that she had more energy and less anxiety. She didn’t need as much coffee to get through the day and felt more motivated. She felt better eating an ultra-processed diet than she had before, a change she attributes to taking in more calories by eating full meals, instead of haphazard combinations of whole-food ingredients.

How could two people eating the same type of foods have such different experiences? And could it be true that not all ultra-processed foods deserve their bad reputation?

These hotly debated questions come at a crucial moment. In 2025, the U.S. government will release an updated version of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which tell people what they should eat and policymakers how to shape things like school lunches and SNAP education programs. The new edition may include, for the first time, guidance on ultra-processed foods. Officials at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are also reportedly weighing new regulatory approaches for these products.

The food industry, predictably, maintains that ultra-processed foods have been unfairly demonized and can be part of a healthy diet. Likely sensing a threat to their bottom line, large food companies have reportedly already started lobbying against recommendations around processed-food consumption.

What’s more surprising is that even one dietitian would take their side, defending a group of foods that, according to 2024 research, has been linked to dozens of poor health outcomes ranging from depression and diabetes to cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairment. Wilson has endured plenty of criticism for her position, which is not popular among the nutrition-science establishment. But she stands by it. Sweeping recommendations to avoid all ultra-processed foods stand to confuse people and make them feel bad about their diets, Wilson says—with questionable upside for their health.

What is a processed food, anyway? It’s a rather new concept. Foods are mainly judged by how many vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients (think fat, protein, and carbs) they contain, as well as their sugar, salt, and saturated-fat contents. There’s no level of processing on a food label.

Scientists don’t agree on exactly how to define processed foods. If you give two experts the same ingredient list, “they will have different opinions about whether something is processed or not,” says Giulia Menichetti, a faculty member at Harvard Medical School who researches food chemistry. Take milk. Some experts consider it a processed food because it goes through pasteurization to kill pathogens. Others don’t think it belongs in that category because plain milk typically contains few additives beyond vitamins.

The most widely used food-classification system, known as NOVA, uses the latter interpretation. It defines an unprocessed food as one that comes directly from a plant or animal, like a fresh-picked apple. A minimally processed food may have undergone a procedure like cleaning, freezing, or drying, but hasn’t been much altered from its original form. Examples include eggs, whole grains, some frozen produce, and milk.

Under NOVA, a processed food contains added ingredients to make it taste better or last longer, such as many canned products, cured meats, and cheeses. An ultra-processed food, meanwhile, is made largely or entirely from oils, sugars, starches, and ingredients you wouldn’t buy yourself at the grocery store—things like hydrogenated fats, emulsifiers, flavor enhancers, and other additives. Everything from packaged cookies to flavored yogurt to baby formula fits that description.

“You end up with a system where gummy bears and canned kidney beans” aren’t treated so differently, says Julie Hess, a research nutritionist with the USDA. At the end of the day, they’re both processed.

Why should that matter to anyone aside from researchers and dietitians? Because most people who care about their health have the same question about processed foods: Are they killing me? And right now—despite their looming possible inclusion in dietary guidelines—no one really knows the answer. There’s limited cause-and-effect research on how processed foods affect health, and scientists and policymakers have yet to come up with a good way to, as Hess says, “meaningfully delineate between nutrient-dense foods and nutrient-poor options”—to separate the kidney beans from the gummy bears.After her experiment last summer, Wilson also continues to eat plenty of processed foods—and to feel good about it. To her, the debate is about more than food; it’s also about the realities of living in a country where grocery prices are spiking and lots of people simply don’t have the resources to eat three home-cooked meals made from fresh ingredients every single day.

“People often assume that a dietitian’s day is telling people to eat less,” Wilson says.

But she says she spends far more time helping people figure out how to eat more—whether because they’re trying to feed a family on a tight budget or because they simply don’t have time and energy to cook—and how to add nutrient-rich foods to their diets in a way that’s affordable.For some of those people, ultra-processed foods may be the difference between going to bed hungry or full, Wilson says. She’d pick full every time.

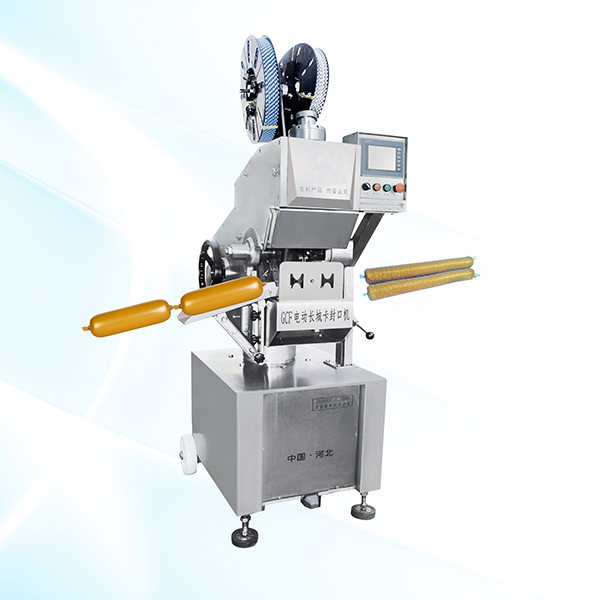

Hebei Hanruisi Technology Co.,Ltd.Is a company specializing in the production and sale of shock freezer, meat processing machines, sausage casing and sausage aluminum wire clamp in China, and is famous for its excellent quality and favorable prices.